The Anti-Democratic Attack on Higher Education

A Q&A with CDAF fellow Eve Darian-Smith on her new book.

As one of the small number of non-academics among the fellows of the Center for the Defense of Academic Freedom, I’m continually impressed with how much my fellow fellows from academia know, and how deeply they’ve thought about issues in their areas of expertise.

They are the best examples of what it means to be a scholar, an expert who engages in the practice of deep inquiry, and then the work of conveying the results of the inquiries to a wider audience.

It’s a pleasure to be able to use this platform to highlight some of the highly relevant work by these scholars and its connection to defending academic freedom.

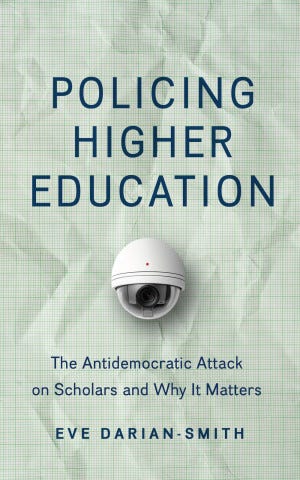

CDAF fellow Eve Darian-Smith’s imminently forthcoming book, Policing Higher Education: The Antidemocratic Attack on Scholars and Why It Matters (JHUP) could not be more attuned to this moment.

As we see in the Q&A below, the present crisis in higher ed has both deep and broad roots, and, in my view, acknowledging and addressing these roots are the only way to move forward toward a system of post-secondary education that is accessible and oriented around the interests of free people in a democratic society.

Here’s something else: I felt better after reading Eve’s answers to my questions. It reminded me that, as dire as things may appear in the moment, we can and do understand the problems and challenges. We have a good idea of what needs to be done.

Now we need to do it.

Eve Darian-Smith is a Distinguished Professor and chair of the Department of Global and International Studies at the University of California, Irvine. She is an interdisciplinary scholar trained in law, history, and anthropology. She is an award-winning author and teacher and has published widely, including 7 books and 7 edited volumes. Her latest book, Global Burning: Rising Antidemocracy and the Climate Crisis (2022), won the Betty & Alfred McClung Lee Book Award and silver medal in the environment section of the IPPY Awards.

There will be a virtual book launch, where we’ll get to hear from Camilla Croso (executive director, Coalition for Academic Freedom in the Americas), Karin Fischer (senior writer, Chronicle of Higher Education), Milica Popović (senior postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Culture Studies, Austrian Academy of Sciences and former project lead at Global Observatory on Academic Freedom, Central European University in Vienna), Barrett Taylor (professor and coordinator of higher education, University of North Texas, CDAF fellow), and Jeremy Young (senior advisor, American Association of Colleges & Universities).

Policing Higher Education: The Antidemocratic Attack on Scholars and Why It Matters Tuesday, May 13, 6:00 pm ET

Register here for a virtual discussion on Eve Darian-Smith’s new book Policing Higher Education: The Antidemocratic Attack on Scholars and Why It Matters.

—

John Warner: Given the reality of the book proposing, writing, and publishing process, it’s obvious that Policing Higher Education has been in the works for a long time, and yet here we are in the midst of a genuine emergency in terms of the assault on higher education. The roots are deep and reach far back into history. Help us understand some of the forces that have led us to this moment.

Eve Darian-Smith: First, John, a big thank you for inviting me to talk about my new book. Regarding your question, yes, we are in a genuine emergency, and we tend to think that the current crisis is something new that arrived out of nowhere, leaving many people asking with disbelief, “how could this have happened?”

In my book, I point to the structural drivers that have developed over time and lie behind the federal assault on colleges and universities today. The rise of antidemocracy, both here in the US and elsewhere, and the appeal of far-right political figures, is a consequence of various economic and political factors. Higher education has become entangled within a global shift in which free-market fundamentalism as the dominant economic framework is being seriously challenged. Today, more and more people are questioning the neoliberal ideology and extractive capitalism that has created a world of massive social injustice over many decades. This is related to huge instability in the global political economy and unprecedented inequalities within and between nation-states. Particularly in the global south, people are experiencing extreme conditions of disenfranchisement, disempowerment, food insecurity, conflict, dispossession, and a sense of being abandoned by their national leaders.

In the US, we are also experiencing these impacts with decreasing wages and the shrinking of the middle class that has been happening since the 1970s. There is a general sense that opportunities are diminishing for the everyday person, while billionaires are amassing extraordinary fortunes and increasing political power. Alongside this material reality, the Republican Party has promoted anti-intellectualism and distrust in government institutions, including institutions of public education for many years. With colleges becoming extremely expensive and corporatized throughout the 1980s and 1990s, they have also become easy “elite” targets to blame for societal disappointments and frustrations. The culture wars, and their racist, sexist, and religious undertones seeking to reinstate White supremacy, have also played a major role in stoking public resentment toward scholars and researchers.

JW: You open the book by discussing how this is not a purely American phenomenon, that we are experiencing a larger global phenomenon where other countries are further down the road in their destruction of academic freedom and access to educational opportunities. Looking over the horizon at those countries, what can or should we understand about what’s going on in the US today?

EDS: That’s a great question. I started writing the book in 2022, although it draws on my research on rising global authoritarianism that I have been doing for over a decade. I was alarmed that what was happening in other countries around the world in terms of attacks on higher education was unfolding here in the United States. This was most evident in states like Florida, Georgia, and Texas. For me, there was a sense of urgency in writing the book and trying to communicate that we may be facing an imminent national threat. Unfortunately, as you say, here we are today. What we are now experiencing is a truly extraordinary attack on colleges and universities, and an explicit effort by the Trump administration to dismantle higher education – as we know it – altogether.

Looking at what has happened in other so-called democratic countries such as Hungary, Poland, Brazil, India, and so on suggests that we should be very concerned. In these countries, the higher education sector has been directly attacked by the far right, and many universities have been widely censored. Overseeing curriculum, harassing faculty, surveilling classroom discussion, defunding research, stacking university leadership and boards of trustees with political allies, and, in some cases, establishing new universities run as an outreach of the state – these are some of the ways governments attack universities and their ability to foster the freedom to learn and the freedom to think.

Here in the US, over the first 100 days of Trump’s second term, we have been witnessing similar oppressive efforts playing out in rapid succession. Some international students have had their visas revoked, and some students have been effectively disappeared into detention centers or deported without due process. In addition, almost all college and university leaders have capitulated to executive orders around DEI and threats of defunding, with Columbia University being the most egregiously deferential.

Fortunately, we are also starting to see some pushback as Harvard, with its immense wealth and prestige, weighs in with a legal suit against Trump. This has helped rally hundreds of other institutions to put their name on the American Association of Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) open letter titled "A Call for Constructive Engagement.” How this legal resistance will unfold is still very uncertain. But returning to your question, what is becoming crystal clear is that we are now fighting a full-scale assault on higher education and ultimately an attack on every person’s ability – both inside and outside academia – to think freely.

JW: I don’t want to say I’m exactly surprised by what the Trump administration is attempting to do to our higher education institutions, but I am a little taken aback as to the degree to which they seem to want to genuinely tear the entire system down as opposed to influence it or capture it for their own political purposes. I thought it would be something more like what Ron DeSantis has done to New College in Florida, where he’s flipped the institution to exist according to his particular vision. But the direct attacks on university funding and the shutdown of NSF and NIH grants really seem to be purely destructive. What do you make of this?

EDS: Yes, the intentional destruction – and gleeful cruelty by Trump and Musk at having upended many thousands of people’s lives and futures – is something I was not expecting either. The Trump administration clearly doesn’t care if cancer research is stopped or if people lose years of scientific data that could help save lives in the future. They just don’t care.

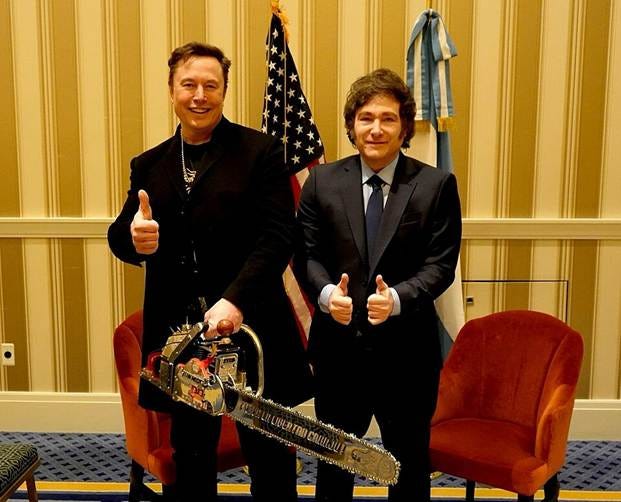

We probably should have foreseen this willful destruction, however, given this is what happened in Hungary under prime minister Viktor Orbán, who came to power in 2010. He steadily eroded the legal system, prosecuted journalists and media, scapegoated immigrants, and forced universities to capitulate or leave the country, which is what the Central European University did when it moved from Budapest to Vienna in 2018. And this happened more recently in Argentina with the election of far-right president Javier Milei in 2023, whose chainsaw antics Musk so readily emulated. Milei crashed the Argentinian higher education sector in 2024 with severe budget cuts and threats of university audits and faculty firings.

As I argue in my book, Trump, along with other narcissistic want-to-be dictators, form a global cadre that shares strategies and policies (and chainsaws!) about how to shut down democratic political debate and oppress ordinary people. Disturbingly, they seem to get a kick out of creating havoc and playing destroyer.

JW: Your penultimate chapter, “Weaponizing Universities in the Twenty-First Century,” walks us through the last two and a half decades of attacks on the edifice of higher education. To me, it reads like an alternate history to what is still discussed, even by people who decry what Trump is currently up to, of an academy that lost its way by becoming, in their framing, “woke” and hostile to conservative interests. What’s the fuller story you want to tell?

EDS: The story I want to recover is one that has been deliberately erased from the public imagination. In focusing on “woke” narratives that link today’s faculty and students with the disruptive events of the 1960s, conservatives conveniently leave out the Republican backlash against the civil rights movement. This backlash included FBI on campus, surveillance of speech, and sending the National Guard onto campuses that traumatized many students and left some dead in the case of Kent State University and Jackson State University.

Less dramatically, the weaponization of the university shifted gears in the 1970s toward the steady takeover of higher education through more managerial processes. This involved the corporatization of public education, evidenced in a decline in shared governance with faculty, a growing number of adjunct and temporary instructors, and a bloated class of university administrators. It also included university and college dependency on federal funding for research, in turn creating greater vulnerabilities for external political oversight and control.

But it is in the twenty-first century, with events surrounding 9/11 and the war on terror, that the militarization of the college community again became explicit. There was a renewed police presence on many campuses, with officers wearing military-style uniforms and weapons distributed through the federal 1033 Program. There were also greater efforts to control what could be taught in classrooms. Big Oil and other economic interests donated large sums to focus research on money-making areas such as energy, security, defense, and technology, away from critical research examining issues of class inequality, racial discrimination, and the looming ecological crisis.

So, it’s not that universities and colleges have become antagonistic to conservative issues, as Republicans would tell it. Rather, Republicans and related political allies, think tanks, philanthropists, and extremely wealthy alumni and trustees have been fighting to control what can be studied and taught for decades. Their efforts to quell the freedom to think became even more aggressive in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in 2020 that ignited the global Black Lives Matter movement that saw huge student protests on many college grounds calling for police accountability and a stop to racial profiling. In sum, conservatives were able to partly “capture” the minds of the university community in the past, and they are aggressively trying to do so again. They know that a lot of money and power are at stake. In my book, I call this an effort to “recolonize” or reoccupy the thinking of a new generation of students and control what they know and how they think.

JW: The last chapter is on “fighting back.” While the current moment feels like (and probably is) a genuine crisis, the truth is that reclaiming a robust higher education sector that benefits society is going to require short-term fighting combined with long-term rebuilding. In your view, what do these two needs look like? What should we be doing now? What should we be thinking about long-term?

EDS: When facing the emergency surrounding higher education, it is important that we don’t feel despondent and without purpose or agency. I appreciate that for many this is very hard, particularly for students and adjunct lecturers with short-term teaching contracts. But if every faculty member decided on a collective action, such as a peaceful noon-time protest, it would make a massive statement of shared defiance. I know that efforts for such collective action among faculty organizations, faculty unions, and other labor groups are happening. But I also know that many faculty are still hesitant to participate, thinking hopefully that their research will be funded by a wealthy donor or convincing themselves that protest is a waste of time. But I argue that scholars can no longer hide behind their microscope or data set or in the archives. The time to act is now. And frankly, if Harvard goes down, I fear that everyone in higher education will be facing a very different future in the coming years that may not be recognizable – unless of course you are a scholar who has had to flee Turkey, Hungary, India, or other antidemocratic countries.

Long-term, we must also think about rebuilding a new kind of public higher education sector that is more accessible to middle- and working-class students and more receptive to intellectually diverse and culturally pluralist worldviews. In my book, I outline five ways to foster a more equitable and meaningful revisioning of higher education. But my underlying message is we must lift up the idea that colleges represent a collective social responsibility that explicitly serves the best interests of students as well as wider societies beyond campus grounds.

JW: Finally, a question I ask in all of my Q&As with authors be they here or my personal newsletter: What’s one book (on this or any other subject) that you think people should know but which they might not be familiar with?

EDS: There are so many good books out there! But a book that stands out for me, and is related to our conversation about attacks on the freedom to think, is called The Memory Police. This is a fictional tale by the Japanese author Yōko Ogawa, written in 1994 (translated into English in 2017). It describes in haunting language the slow erasure by the police of people’s memory of everyday objects and associated feelings. Evoking the writings of Kafka and Orwell, it is a disturbing tale of insidious disappearance, including the disappearance of the main character’s limbs, body, face, and ultimately their mind.

The views expressed in this newsletter are those of individual contributors and not those of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) or the AAUP’s Center for the Defense of Academic Freedom.