Every Generation Has Moments Like This

Q&A with CDAF fellow Demetri Morgan on the current state of higher ed and an important new initiative.

The Center for the Defense of Academic Freedom operates as a collection of fellows brought together to collaborate on, in the words of the CDAF mission statement, “preserving and expanding conditions that make it possible to work, teach, learn, create, and share knowledge in ways that promote the common good.”

Some of this work happens in collaboration with each other, but many of the individual fellows are working on these issues in their day-to-day activities and scholarship.

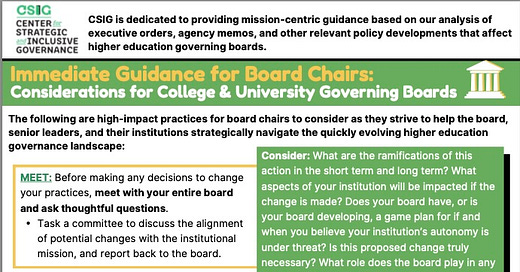

One of the CDAF fellows, Dr. Demetri L. Morgan recently launched a new initiative in collaboration with Dr. Raquel M. Tall of the University of California Riverside, The Center for Strategic and Inclusive Governance. The CSIG is “focused on advancing mission-centric university leadership. CSIG aims to curate open-access resources and strengthen strategic relationships to encourage intentionality and inclusive strategy in decision-making. Strategic and inclusive governance is the way forward, and in a time of significant change, we strive to open doors and foster timely conversations.”

Their first resource is targeted guidance for college and university board chairs and top institutional leadership to help them navigate the current attacks against higher education.

In addition to his work with CDAF and the CSIG, Demetri Morgan is an associate professor at the University of Michigan Marsal Family School of Education with an extensive record of academic research an publishing focused on there role of higher education in a diverse democracy.

I secured a few minutes out of Demetri’s busy schedule to get his take on the current state of things and find out more about CSIG and their advice for college and university boards.

John Warner: The threats to college and university missions and operations at the moment are pretty much unprecedented, right? How do you think we should be thinking about these things in terms of the big picture?

Demetri Morgan: I think it’s sensible to be alarmist right now and for very good reason. But I was reminded the other day in class - that every generation has moments like this. I am teaching ‘College Students in the U.S.’ and roughly speaking, it’s a survey course on how students get to and through higher education. Last week, we were discussing the campus physical environment and a student mentioned that their undergraduate campus buildings were designed during the Vietnam War era protests. It’s been well documented that many buildings that were built during that era were literally designed in ways that were responsive to campus dynamics at the time. I wasn’t alive but I imagine that if university leaders felt it imperative enough to literally build buildings in a way that could deal with protests - they probably felt like it was an unprecedented moment. Which is all to say - I think we need to be able to toggle between staying in the present and understanding history and the broader trajectory. This is a moment that needs to be met but it’s not without precedent. Higher Education has been through McCarthyism, the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Movement, and the COVID-19 pandemic, but as a writer I read recently wrote - we still need to do the work.

JW: You’ve recently started a new initiative to help address these threats, the Center for Strategic Inclusive and Governance that is focused on “mission-centric guidance.” How do you see the framework of “mission-centric guidance” as opposed to other ways of looking at institutions?

DM: Without boring readers – the bedrock of governance from both a legal and best practice standpoint relies on the concept of ‘fiduciary duties’. The three customary duties we talk about in the nonprofit sector are the duties of care, loyalty, and obedience. In particular, the duty of obedience suggests that trustees as individuals and governing boards as a whole are responsible for ensuring institutions are obedient to relevant laws, policies, and their institutional mission. Often, people stop at obedience to laws and policies – but an institution’s reason for being emanates from its mission, not laws and policies. So, we believe that in this era – good governance has to be mission-centric in how it approaches laws and policies. By mission-centric – we mean that institutions take seriously what they purport to be about and do and use that to guide their stance and actions as a foremost point of consideration. As has been famously said, not all laws [and policies] are just, and being mission-centric can help institutions parse out how to navigate forward in ways that advance their institution's ability to serve students, faculty, staff, and the broader community.

JW: Your first release with guidance is targeted toward college and university board chairs and governing boards. Why start there? What important or unique role do these people/entities have at this time?

DM: Boards have the ultimate responsibility for the institution's well-being (aka they are fiduciaries - hope you were paying attention above!). I explain it to my non-higher education friends by comparing the governing board to an interest-bearing savings account you place in a bank. You expect that when you return for your deposited funds, that not only will it be there but there will be additional income to show for it. Similarly, governing boards hold an institution's charter or incorporation papers and are tasked with ensuring that institutions operate sustainably, fulfilling their missions for as long as possible. (Side note: this is why institutions can’t just “spend their endowment” during financial crisis - it would harm the institutions long-term sustainability). Of course, Boards hire a chief executive and delegate power and authority to that role; however, the governing board ultimately maintains oversight and responsibility for the institution and all its assets, both tangible like the physical plant and intangible like its reputation and institutional autonomy. But, since Board’s are not involved in the day-to-day operations (and ideally shouldn't be), they can, like a savings account, become out of sight and out of mind. Most people also assume because most trustees are wealthy and successful in other areas of their life - that must mean that they are supremely capable to help run complex institutions. My colleague, Dr. Raquel M. Rall (UC, Riverside), and I believe we must recommit to supporting and training trustees for current and future challenges. Trustees are talented and successful but very few have experience in education - and there’s no governing board certification that can signal that someone is well-prepared for such a prominent role. And even if you had a group of amazing trustees as individuals - they still have to work as single unit - in partnership with a range of senior institutional leaders and overcome all the group dynamics that plague any group of diverse individuals. While there are numerous resources, societies, blogs, and communities available for faculty, administrators, and leaders, we think there is a need for additional resources that are tailored directly for Boards. Our goal with CSIG is to provide timely resources and guidance for trustees and governing boards interested in effectively aiding their institutions.

JW: Your guidance is specifically targeted towards governing boards, but I’m guessing it’s useful for those of us who work in higher ed institutions but are not necessarily in those roles to still understand this guidance. Why is that the case?

DM: I love this question because of the critical role boards play; everyone on campus is affected by their decision-making and vice versa. One reason we are sharing our resources freely and widely is that we believe it is helpful to humanize the challenges governing boards are facing and encourage others to think strategically since much of what institutions do (or don’t do) is interconnected with what is going on at different levels. Now is the time for institutions, both within and between, to come together to navigate current challenges, and this is best achieved when information is shared. I am not saying feel bad for board members - but understanding what’s on their plate and what is at stake for them may be a small way of figuring out how to work better together.

JW: I’m not going to put you on the spot or pretend any of us have a crystal ball, but what are your thoughts on how this is going to play out? What, in your view, can governing boards and institutions do to hold space for institutions to do the work they’re meant to do? (Feel free to repeat anything from the release here, though we’ll also link it.)

DM: We’ve seen this playbook from the tech sector: “move fast and break things.” Things are breaking, and the speed is dizzying, so we are well underway. Similar to the inaugural post for this newsletter, obeying in advance is one of the easy ways to give away autonomy that may never return. I suspect the courts will continue to weigh in. There will be some judiciary wins and losses, but all of that will take time. Not only for decisions but for interpretation and implementation. Therefore, it is prudent for governing boards and senior leaders to set up internal structures (beyond websites about recent executive orders) to triage and strategize about how to respond—or not— to what is coming at higher education. Of special emphasis - we hope that in these movements, leaders will consider the impact and fallout of any given decision in these times for as many constituents as possible. What is the worst that can happen and for whom? We also think it’s important to resist the temptation, as one Substack I follow put it, to “swing at every pitch.” Yes, there is a lot happening, but institutions cannot and should not engage with everything that is out there. Issues that run afoul of the institution's mission and its sustainability (like what we are seeing with the response to the NIH cuts and vague attacks on diversity, equity, and inclusion) must be responded to vigorously. We also suggest “counting the costs” of changes (for example, check out how plaintiff institutions quantified the impact of the NIH cuts). How many people are losing jobs? How many person-hours are spent scrubbing syllabi and websites? What specific clinical trials are being stopped? Who is being harmed? If changes are made in response to federal and state directives and it seems like there was no cost (human or economic), then it reinserts baseless narratives that higher education is or was bloated and not doing anything of value. As most reasonable people know, improving any organization, much less an entire sector is nuanced and complicated. Higher education is rife with challenges – no one is suggesting otherwise but it has done and continues to do an immense amount of concrete good both locally and more broadly. So if leaders of institutions are not both strategic and inclusive in navigating this moment, I fear not for the well-to do institutions—but those that have been teetering but still do great work within their regions and with a broader array of students. It’s incumbent then for the well-to do institutions and their leaders to do all they can in both visible and less visible ways to stand up for what’s best about higher education and continue to creatively and collaboratively work on addressing the issues that plague our sector.

Thanks to Demetri for his deep insights, and please see the full text of the CSIG guidance for college and university governing boards, right below this sentence.

The views expressed in this newsletter are those of individual contributors and not those of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) or the AAUP’s Center for the Defense of Academic Freedom.

I'm sorry but the headline on this piece is delusional. The threat to Trump Administration poses to academic freedom is of an order of magnitude greater than anything previously seen. There hasn't been anything remotely this dangerous since McCarthyism.